The never-ending rabbit hole of microgenres

Written by Jenna Dreisenstock

‘To define is to limit.’

Once said by the ever-flamboyant Oscar Wilde in his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray: Wilde’s character Lord Henry wove into the the sweet-blonde curled Dorian, that allowing ourselves to fall victim to the ever defining boxes of society, in which we prevent ourselves from indulging in our oh so-very human senses: the most important of all, refusing the true let-go into temptation we are limiting ourselves. We are defining ourselves into categories where we directly prevent experiencing the true nature of things, and therefore those limitations lead us into a hollow ennui. However, perhaps it’s important to mention that Dorian ended up as a delusional, frantic murderer stemming from his own selfish indulgence. Anyway.

In talking about the complexity of definition, I would like to explore the ways in which we define genres, the way in which language and tone is forever malleable in the music world. What draws the line between absolutely ridiculous here-are-some-random-words-strung-together-that-sort-of-make-sense-but-not-really and the actuality of a genre. Does creating our own definitions actually allow us to break away from the norms, allowing underground subcultures to flourish and feel an embrace of liberation? In the manipulation of broad genre terms that artists are lumped into, often they don’t always feel as though they belong; however this can be said for sub-genres, and micro-genres. Meta.

The origin of microgenres can be dated back to the 1970’s, in which artists began to string together musical jargon which they felt defined their style more accurately than how they were perceived: as the broad genres in which they found themselves, left them in alienation. Perhaps even without realisation, leaving a sense of loss of personality and experimentation. There are positives and negatives to the ways in which the world of micro-genres have been defined and redefined, but first let’s traverse the blooming obscurity of some of these genres and how they came to be (or how they came to die.)

In no particular order, I have decided to showcase some of the more obscure microgenres as opposed to genres such as Vaporwave, Chillwave or Witch House: if one has more insight into the electronic world, these genres may seem relatively familiar – so I decided to quite literally jump down the rabbit hole and swirl into an eclectic frenzy of microgenres which has possibly left me mid-existential-crisis.

That being said, let’s take a look into the microgenres of the electronic world and explore definitions and non-definitions:

Electroclash

With many of these microgenres soaked in an eccentric visual aesthetic, Electroclash is (or, was, rather) a genre that relied heavily on gritty, avant-garde, leather bound and feather-boa performances; a seductive indulge of the senses and a saccharine delve into the cigarette-drenched glittering of a dingy bathroom hangout, in which backseat sex and the grimey (sparkling) surfaces lined with <insert drug name here> – sparking beautiful people bound in aesthetic glamour and electro-engulf performance-art with an OTT sense of humour to accompany the movement. Pioneered in the 1990’s by Dutch producer I-F with his 1997 track ‘Space Invaders are Smoking Grass’, the movement broke through as a response to what the early artists felt was a ‘rigidity’ in the structure and style of techno music at the time: a break away from the norm in which multiple genres such as synth-pop, punk and techno (and I could go on) were woven into a free-spirited, upbeat mesmer of experimentation, bracing the club scene at a pivotal moment in the early 2000’s. Electroclash’s birth in the 1990’s lead to the genre’s peak in the early 2000’s, yet traces of this micro-genre are still listed as an influence for artists today.

Folktronica

True to its namesake, Folktronica is what it is, the title itself a relatively obvious insight into what we may come to expect from artists of this genre. In true microgenre fashion, the creation of the genre label grew from self-identification – almost, a humorous manipulation of language and what is to be defined as valid definition, and what is defined as invalid definition. If there is such a thing as an invalid definition of a musical genre, language and musical jargon is something that evolves with time and is basically, completely made-up. Folktronica combines elements of string drenched folk and indie love, a sweet companionship between the acoustic pluck or even the enthusiasm (or melancholia) of a banjo as the traditional intimacy of the folk-genre lends itself to catchy, melodic synth-hooks, upbeat tempos and lush landscapes: a blend of the tenderness of folk or indie-pop amongst textural electronics and synthesizers to a faster-paced dance. Artists such as Caribou and Múm are modern examples of artists considered to ‘fit the label’ yet Folktronica has its precursors dating further back in time to the early days of the Moog synthesizer, a release which allowed traditionally ‘acoustic’ or ‘rock’ artists to begin experimenting with their own personal sound, yet with the brand new ability to incorporate electronics into a rising microgenre.

Seapunk

As mentioned earlier in the article, many microgenres and underground music subcultures are inherently tied in with a certain visual aesthetic which makes them pop vivid eccentricism and sparking entirely new perspectives – standing out and becoming a cult-like kaleidoscope of imagery and auditory journey. Seapunk is probably one of the most poignant examples of this. Seapunk quite literally started off as a visual, vividly brilliant and strange aesthetic meme, fueled by the #Seapunk hashtag which made its debut on Twitter in 2011, and popularized further in cult-like communities deep within the realms of the ever strange, ever evolving and artistically absurd blogging site Tumblr. With an integral tie between the visual aesthetic of the genre and the auditory experience, Seapunk’s electronica-R&B-dance-pop-experimental-glitch (and so on and so forth) mish-mash creates a brilliant whirl so filled with colour and texture it’s inviting texture seamlessly weaves with it’s visual aesthetic: as the name may suggest, the imagery association revolves around that of the ocean, with CGI palm trees and dolphins floating dreamlike in swirling ice-creams of pinks and blues, warping shapes and colours that mold into one another like neon-clay, cyberpunk glitter and a nostalgia focus on 90s imagery; the collage of Windows ‘95 text boxes and icons, and aforementioned (relatively terrible) CGI beach-themed, ocean soaked retro aesthetic. Born from an internet phenomenon, Seapunk was a pioneering process in the development of a more well-known sub-genre: Vaporwave.

Lowercase

Lowercase music, unlike the other genres on this list, is heavily focused on minimalism and ambience – the imagery that comes to mind is the clinical white of a blank page, or the flickering fluorescent light that should have been fixed months ago; a creaking wooden floor or the sound of a tap dripping. With that being said, Lowercase is the amplified version of everyday, minimalist sounds into an arranged structure: a structured ambience even more ambient than actual ambience. Ironically, one of the most striking aspects of this genre is its uses of lengthy silences amidst seemingly random, quiet samples: which begs the question, how much ambience is too much ambience that it literally crosses the border of no longer being defined as music? Lowercase is all about pushing the often unheard sounds to their most unheard of amplification, and exists in a niche in which the quiet makes itself heard – quietly.

Shibuya-Kei

An (ironically) all-encompassing microgenre, Shibuya-Kei was born in the early 90’s in Japan partly in response to the far-reach of 60’s Western music gracing the East in a new and exciting fashion: while still containing a sub-culture of Japanese aesthetic. Shibuya is one of 23 special wards of Tokyo, known for its radical concentration and aesthetic, filled with stylistic, artistic as well as elegant venues, record and book stores and its reputation as a nightlife culture-hub. Shibuya-Kei has been described as a post-modernist response not only to Western music which was gaining traction, but with the J-Pop and J-Wave terms coined earlier in the 80’s. Shibuya-Kei was created out of the aestheticism of Japanese consumerism. The bright neon lights and busy hussle of Tokyo culture bred this cut-and-paste hybrid of genres into one; Shibuya-Kei ranging from everything to tracks inspired by Western pop or rock & roll, to Latin bossa-nova; funk and jazz – and in this sense upbeat synthwave and chiptune electronica. Although the genre peaked and died down within the 90’s, Shibuya-Kei’s influence on music is still present – a nostalgia pixel art soaked in bright-light glow, Shibuya-Kei spilled over into the West too, spawning bands and artists like Anamanaguchi and Momus.

There is a long-ranging debate about the use, creation and relevance of genres; we as humans tend to arrange things carefully in metaphorical boxes – to compartmentalise them. Boxes in which we hope everything will make just a little more sense as now, with a label we are able to identify and understand. Sorting the world into boxes and labels helps us to feel as though we have elements of control, yet living within those boundaries there are many questions that need to be considered. Whether it’s the use of language, our twisted and bended specificities of what is or isn’t a music genre, or the question as to how, if and when we should be using labels. Does categorizing ourselves in such labels trivialise the complexity of music or liberate us in personal reflection of how we feel about what we create?

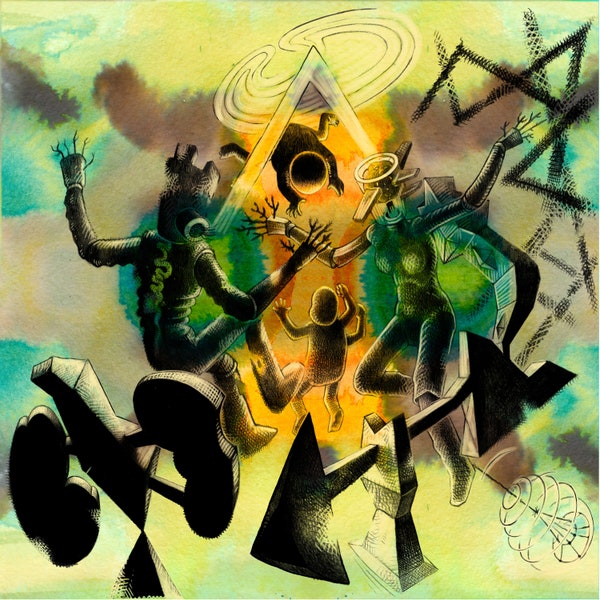

[Image credit: CUBEGHOST]

Leave a Reply